“This is the only place we should be in”: Anti-zionist Jewish Students Claim a Space for Sukkot on Another Columbia Lawn.

Students built a sukkah to celebrate a 7-day-long holiday in solidarity with Gaza and Lebanon.

By a Grassroots Magazine writer

Photo by Eric Santomauro-Stenzel

On the evening of Wednesday October 16, a faint echo of singing carried throughout Columbia’s campus. On the lawn in front of the mathematics building— on the northside of Columbia’s Morningside campus—four students sat under a tree, leading a wider crowd of about thirty people.

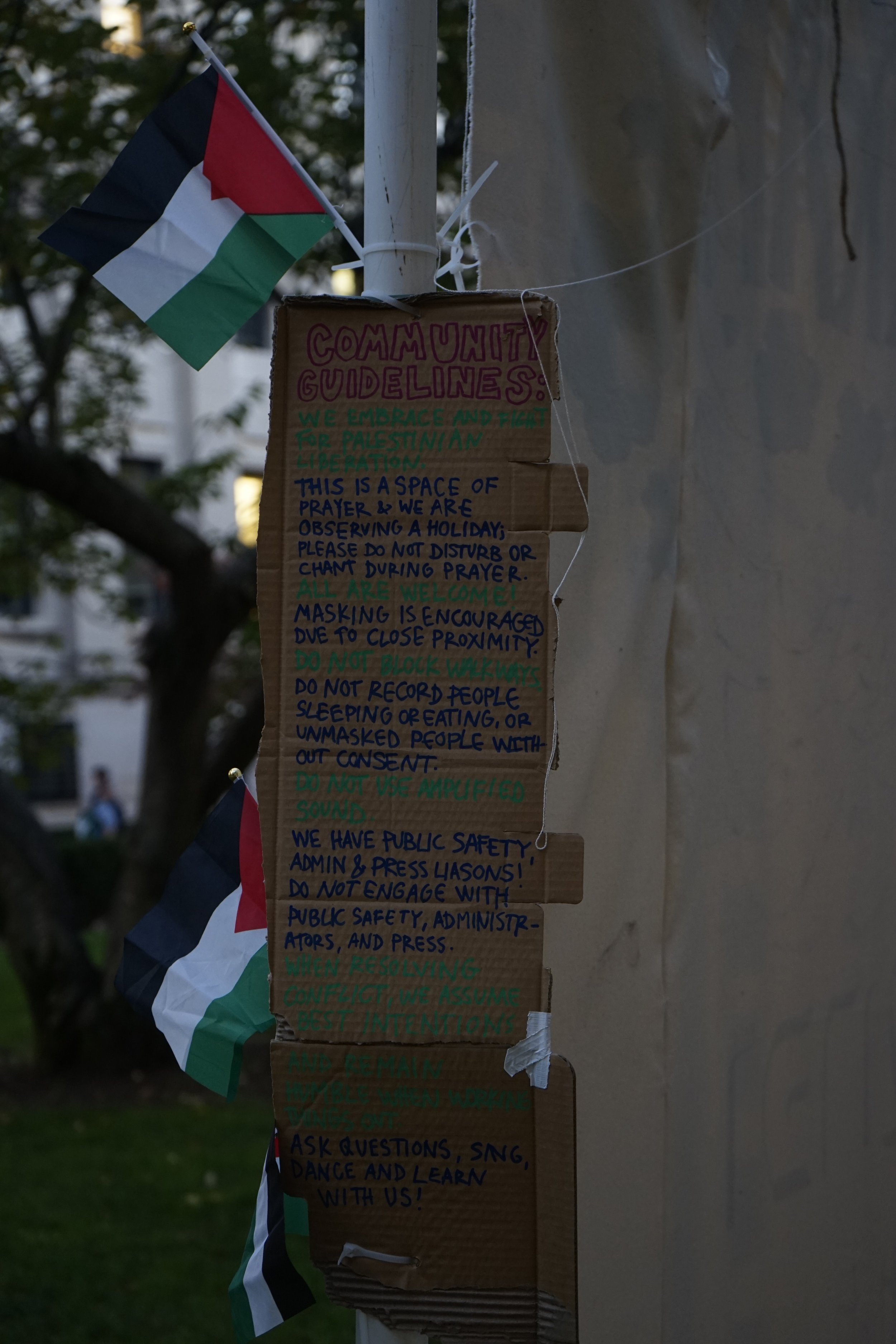

The lyrics sang “We shall not underestimate our power” and “Where you will go, I'll go my friend”. Next to them, people set up a simple cubic structure, made out of white tubes, topped with thin, wooden garden fences. It was the first day of the holiday of Sukkot. In Judaism, the holiday celebrates the end of the harvest season and commemorates the Jewish people being given shelter by God during their exile in the desert. The Sukkah is a structure built at the start of the holiday, which is used to honor the holiday’s commandements and celebrate in community.

The students, which identified themselves as “an autonomous group of anti-zionist jews,” decided not to participate in the activities planned by the university and other Jewish associations on campus. They built their Sukkah without an official authorization. They did so, they explained, in solidarity with Palestine and Lebanon. They say this action honors the significance of Sukkot as a holiday dedicated to giving shelter and opening up to the stranger, in a moment in which many in Gaza, Lebanon are displaced by Israeli bombing and ground operations.

The students envisaged the space as a place that would go beyond religious observance. “We are hoping to use the sukkah not only as a space to practice our religion, but also use it as a place to have programming and events for community building” Tali, a press liaison for the group. Students like Tali chose to only share their first names out of safety concerns.

Tali specified later that they thought of those events as an opportunity to educate attendants, both Jewish and non-Jewish, on the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and the history of the occupation of Palestine.

The sukkah was constructed with the help of small portable ladders and zip ties. Its walls were made up of hand-painted banners. One of them, facing the path were on-lookers observed the construction, recited “Liberation Sukkah”, along with a quote by poet Aurora Levins Morales, “nest under a block of roads that keep multiplying their shelter”. Another, placed on the opposite side of the structure, depicted two trees in a meadow of poppies, with at the center the phrase: “I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED GENOCIDE TO STOP”, from “Intifada Recitation”, a poem by June Jordan.

After finishing setting up the sukkah, the organizers invited the people sitting on the ground around the lawn to join them in a circle, and then under the straw roof of the sukkah.

The audience had grown to some forty people by then, and not all of them could fit within the structure. One of the organizers invited the attendants to get closer. “There is a reason why the sukkah has two walls and a half!” he remarked, inspiring some laughter.

Photo by Eric Santomauro-Stenzel

The organizers then held a short speech, explaining their stance of celebrating the holiday in solidarity with Palestinian and Lebanese people. One speaker explained how sukkot, as a holiday dedicated to shelter in time of exile, shall in their opinion be dedicated to those displaced and killed by the ongoing Israeli attacks against Palestinians in Gaza, and those similarly impacted by the Israeli army’s attacks on Lebanon.

In the same moments in which they were joining in a circle, Al Jazeera reported that an Israeli airstrike killed three in Tayr Debba, a city in the suburbs of Tyre, southern Lebanon.

Reading from a document prepared by the organizers and circulated by the crowd, one speaker said their prayer had been “weaponized to justify violence”. Another commemorated four displaced Palestinian people who were killed, along with seventy who were injured, in a fire set a flame by Israeli bombing onto their tents in the courtyard of Al-Aqsa hospital, central Gaza. Among them was a software engineering student in his twenties, Shabaan al-Dalou, approximately the same age of the audience in attendance at the sukkot celebration.

The students then held a brief religious service, in which the organizers invited all those who wished to do so to join them in prayer, providing a transcription of the service in both Hebrew and English.

“I think that a lot of people did not consider themselves practicing, because they didn't feel comfortable in Jewish spaces, or felt alienated because of their political beliefs”, have found a space where they are brought into the religion” Sarah, a student who was spending time in the Sukkah on the last day of the celebration, explained.

The students kept the sukkah up for the whole length of the holiday, which is seven days and seven nights. The Dean of Religious Life at Columbia University, Ian Rottenberg, was present at the set up of the sukkah and in the hours that followed. He said to the students he was liasoning with other departments of university administration on how to react to the Sukkah’s installment.

Rottenberg passed by the sukkah several times throughout the evening, approaching the students. In their conversation, he mentioned that Columbia University is offering Jewish students sukkot—here meaning the plural of sukkah, the physical space where the holiday is celebrated—in different locations, including one managed by student life in Fairchild Plaza. All of these were university-sanctioned religious services.

Rottenberg cited safety concerns, explaining that the “Liberation Sukkah” had not gone through an event review, a procedure that is normally adopted for events and religious celebrations at the university. Without this procedure, the university could not provide the standard of security normally granted to those events, he explained. He denied his concerns were connected to an association of the Sukkah with the encampments of last year, and did not elaborate on which aspects of the Sukkah could constitute a safety concern.

The organizers of the event, however, said they wanted to gather in a space that was “explicitly anti-zionist”. In the opening remarks of the service, one speaker had said that they “are here because this is the only place that we should be in.”

Tali spoke to the ambivalence of celebrating sukkot this year. The current situation “makes it obviously hard to experience the full joy of the holiday, knowing that we are sitting here in a shelter” thinking of the “so many people” whose “homes have been bombed, so many people have lost their loved ones, so many people were unable to sit and eat in community with the people they love.”

Students take down sukkah after the last day. Photo by Eric Santomauro-Stenzel

Barnard Hillel and Chabad, two Jewish cultural centers at Columbia, were reached out to for comment, but could not reply in time because of observance of the religious holiday. Rottenberg himself could not, due to time constraints, comment further on the students’ grievances regarding these spaces’ political stance.

The students eventually reached the decision to hold up the sukkah for the remainder of the holiday, but agreed to not spend the night inside it on the lawn. A public safety officer was posted to sit by the sukkah during the day; other officers were seen standing in its vicinity during day hours.

For the students who frequented it the most, the sukkah seemed to serve its function to bring the community together. Shay, one of the participants, said they helped a lot of people with the ceremonies performed during Sukkot. Shay helped them shake the lulav, a bundle of palm, willow, and myrtle branches and etrog, a citrus.

“I think it's really meaningful to see people who otherwise would not have gotten to complete that commandement do it, and to be able to help them do it,” Shay said.

The sukkah’s last day looked much like its first hours seven years prior - only with less people in attendance. Students sat under the garden fences, studying and chatting in the dusk’s golden light. At sundown, a small group of people took down the structure and placed the pieces into metal carts, leaving only an empty patch of grass behind.